This is superb article. A little on the dry side, but worth reading, and it is worth taking the time to study the graphs. I've started the post a few paragraphs into the article so if you want to read the whole thing, click on the link at the bottom...rng

June 22, 2007 | EPI Briefing Paper #191 Reviving full employment policyChallenging the Wall Street paradigmby Thomas Palley |

The Erosion of Shared ProsperityOver the last 30 years the U.S. economy has experienced a sea change in performance defined by the emergence of a disconnection between wages and productivity growth. The disconnection is captured in Figure A, which shows growth of productivity and hourly compensation for production and non-supervisory workers (who constitute over 80% of wage and salary employment). From 1959 to 1979 compensation moved with productivity. Since 1979 productivity has kept growing but hourly compensation has essentially flat-lined.

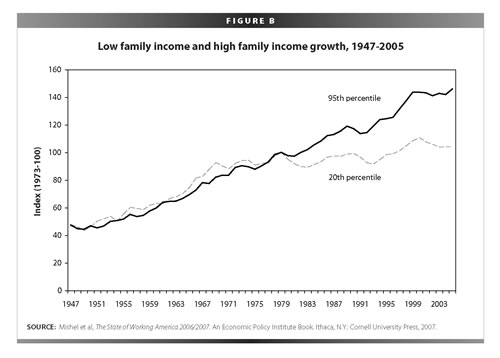

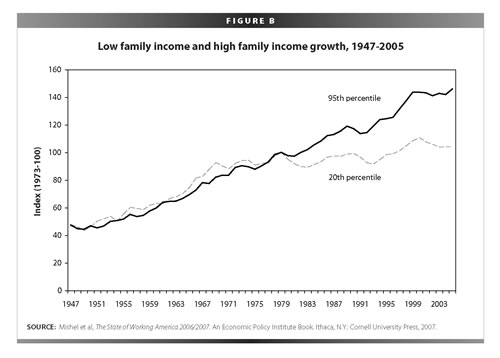

The flipside of the wage/productivity-growth disconnection is increasing income inequality. Figure B shows how family incomes at the top (95th percentile) and the bottom (20th percentile) of the scale grew together between 1947 and 1973. Indeed, family incomes at the bottom of the distribution actually grew fractionally faster than those at the top. Since 1973, however, this situation has been transformed: instead of growing together, the nation has grown apart, with the productivity growth dividend accumulating almost entirely to those in the top 20%—and especially the top one percent—of the family income distribution.

These developments occurred in two stages. Stage one involved widening of wage inequality, exemplified by the CEO-pay explosion. Figure C shows that between 1979 and 2005 CEO pay went from being 38 times average worker pay to 262 times. Stage two has occurred post-2000 and has been marked by a jump in the profit share of national income.

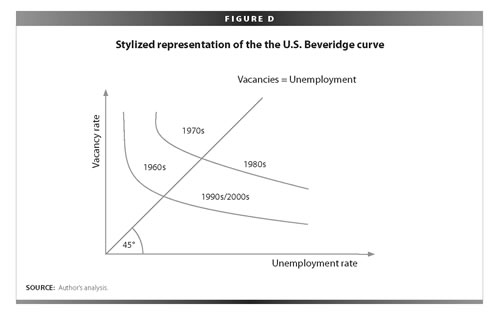

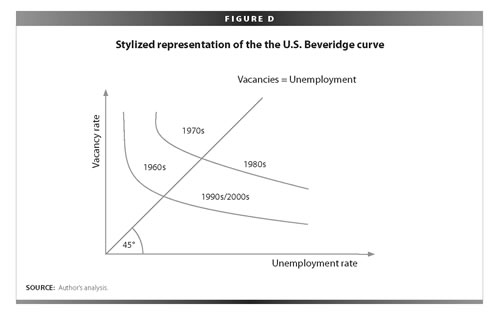

Digging deeper, the disaggregated wage data show that male workers at the bottom of the wage distribution have seen their real wages fall, while those in the middle have seen increases of about 10% spread over 25 years.1 From a cross-generational perspective, male workers at the bottom of the wage distribution now earn less than the previous generation, and their wages also grow more slowly. That means these workers have suffered both cross-generational wage “level” and wage “growth” deterioration. Male workers in the middle of the wage distribution have had some small wage gains relative to the previous generation, but their wages grow more slowly than in the past. They have therefore experienced a cross-generational deterioration of wage growth. This gloomy family income and compensation picture is compounded by other adverse labor market trends. Thus, average Americans are carrying more economic risk in the form of greater job loss risk, greater risk of permanent wage reductions, reduced length of job tenure, reduced health care coverage or increased health care costs, and greater retirement income security risk owing to the shift away from defined-benefit pension plans to defined-contribution plans (Hacker 2006). Macroeconomic Policy and the Erosion of Shared ProsperityThe role of macroeconomic policyThe disconnection between wages and productivity growth has been caused by many factors, including globalization and the changed balance of power in labor markets. But macroeconomic policy has also played a significant role through its impact on overall economic performance. Moreover, there also has been resistance to new policies that could have moderated or altered these trends. As such, policy has been marked by both sins of commission and omission. The current policy regime accommodates a new type of business cycle that emerged post-1979, in part due to policies of financial deregulation and global economic integration. This new type of business cycle is financially driven by asset price inflation and borrowing, with cheap imports helping contain inflation. This kind of cycle contrasts with the pre-1979 business cycles that rested on wages tied to productivity growth, full-employment, and high rates of capacity utilization that provided an inducement to invest.2 This new business cycle has, in turn, called forth a new macroeconomic policy regime. Thus, whereas the pre-1980 macroeconomic policy regime can be viewed as having put a floor under labor markets, the post-1980 regime implicitly puts a floor under financial markets.3 With regard to specific failures of macroeconomic policy, two standout: the first concerns monetary policy and the setting of interest rates, while the second concerns exchange rates and policy attitudes to the trade deficit. Additionally, fiscal policy has been problematic with regard to its impact on after-tax income inequality, and its response to the 2001 recession was particularly poorly designed. In the post-World War II era the Federal Reserve’s macroeconomic policy goals have always been a combination of full employment and price stability. During this era all Federal Reserve chairmen have wrestled with the problem of inflation. However, since 1979 there has been a significant shift in emphasis toward concern with inflation. The new regime manifests itself in several ways, the most noticeable feature of which is the prominence given to combating inflation. This has replaced earlier concerns with full employment, easy job availability, and rising real wages. Indeed, rising wages are actually viewed as cause for concern on the grounds that they may be inflationary, but the same standard is never applied to rising profit rates. The impact of this shift in macroeconomic policy is captured in Figure D, which shows the U.S. Beveridge curve that relates job vacancies and the unemployment rate. The 45-degree line splits the diagram in half, and regions above the line correspond to conditions of relatively full employment since the vacancies are high relative to the unemployment rate. Figure D shows that, whereas in the 1960s and 1970s the U.S. economy operated at a high vacancy-to-unemployment rate, this has been reversed since the 1980s.

The Beveridge curve shifted adversely in the 1970s and 1980s (Bleakley and Fuhrer 1997). Part of this shift was due to demographic factors and the entry of the baby-boom into the workforce, which tended to increase job market churn. However, part of the shift can be attributed to policy, particularly the lack of attention to exchange rates and manufacturing. This contributed to waves of job loss in manufacturing, which created pockets of structural unemployment that have taken years to erase. A second critical contribution of macroeconomic policy concerns exchange rate policy, whose impact is felt in the trade deficit and manufacturing employment. The new policy regime has the Federal Reserve and Treasury turning a blind eye to the foreign exchange value of the dollar despite its critical impacts on manufacturing employment and the trade deficit. Indeed, the Fed has even tended to view an over-valued, “strong” dollar as a bonus that helps contain inflation by putting the squeeze on prices of manufacturing goods. Meanwhile, the Treasury has pursued a form of “exchange rate populism” whereby an over-valued dollar results in cheaper consumption good imports, which buys public acceptance of international economic policies that erode wages and manufacturing employment. The formal economic rationalization of this neglect of the trade deficit is that the deficit supposedly represents the decisions of “consenting adults” who are making consumption and investment choices that maximize their economic well-being. The putative logic is that economic agents are taking advantage of new opportunities for exchange created by trade agreements that have fashioned a global market, and if that results in a trade deficit, then so be it. This policy stance contrasts fundamentally with the policy that prevailed in the pre-1979 era, and it reflects the changed character of the American economy’s business cycle. Today’s economy is fuelled by credit expansion and asset price inflation, with cheap imports helping contain inflation. The pre-1979 business cycle rested on wage growth tied to productivity and full employment, which together fuelled consumption and investment spending. In that earlier regime, trade deficits represented a leakage of aggregate demand that undermined the virtuous circle whereby robust domestic market conditions promoted investment and capacity expansion. Trade deficits were therefore a problem, whereas now policymakers view them as assisting with control of inflation. The natural rate of unemployment4Ideas have played an important role in driving these changes, promoting a retreat from full-employment policy on the grounds that it is not needed and that activist stabilization policies may actually worsen outcomes. No idea has been more influential than Milton Friedman’s (1968) theory of a natural rate of unemployment.5 Friedman’s natural rate of unemployment challenged the earlier view that there existed a trade-off between inflation and unemployment, and that the Federal Reserve could lower unemployment by enduring slightly higher inflation. Instead, Friedman asserted that the economy automatically and quickly gravitates to a natural rate of unemployment, determined by the economy’s institutions. Moreover, that rate cannot be affected by monetary policy, and attempts to use expansionary monetary policy to push unemployment below the floor set by the natural rate will be unsuccessful and only generate ever-accelerating inflation. This claim regarding the ineffectiveness of monetary policy and the absence of a long-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment has been hugely influential in shaping policy choices on monetary policy. First, the claim of policy ineffectiveness has contributed to abandonment of earlier concerns with full employment. The logic is that, since monetary policy cannot have lasting effects on employment, trying to use policy to secure some concept of full employment is a useless exercise. In other words, employment and full employment should not be the focus of policy since they are simply beyond its reach. Second, the claim that monetary policy cannot affect unemployment and only affects inflation leads to a focus on inflation. And because inflation is considered detrimental, that pushes the case for price stability or zero inflation. For much of the 1990s the Alan Greenspan-led Fed explicitly talked of price stability being the long-run goal. However, after the brief flirtation with deflation during the recession of 2000, the Fed has now settled on a 2% inflation target to leave itself room to lower real interest rates in economic downturns. Third, the theory of a “natural rate” provides the Fed with cover when it comes to questions of wage and income distribution. According to the theory, real wages are determined in the labor market and are completely unaffected by Federal Reserve policy. Thus, the Fed may lament wage stagnation and worsening income distribution, but it bears no responsibility, nor can it do anything about it. Indeed, the situation is even worse because of the Fed’s asymmetric approach to nominal wages. When wages lag prices, the Fed sits on its hands, albeit with expressions of sympathy for workers. However, when wages outrun prices, the Fed stands ready to raise interest rates on the grounds that rising unit labor costs are inflationary. This creates a monetary policy trap for real wages and has macroeconomic policy supporting a higher profit share—something that is also supported by current labor market and international economic policy. Fourth, the theory of the natural rate contributes to driving the so-called “labor market flexibility” agenda that attacks unions, the minimum wage, and employment and worker protections. The logic is that these institutions prevent wages from adjusting downward, and thereby increasing the natural rate of unemployment. This explains opposition to the minimum wage by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. Since the Fed adheres to natural rate theory, the Fed implicitly places its weight and influence behind the labor market “flexibility” agenda. The theory of the natural rate has been extensively criticized on both theoretical and empirical grounds (see Galbraith 1997; Palley 1999 and 2007). At the theoretical level it makes grand, unrealistic assumptions about wage flexibility and the way labor markets work, and at the empirical level it has been impossible to establish a tight, stable estimate of the natural rate. Thus, empirical estimates at any moment in time vary enormously, and the average estimate tends to track the actual rate of unemployment (see Staiger et al. 1997). The one clear theoretical prediction is that anticipated monetary policy should have no impact on unemployment and output. Yet studies have repeatedly found that this is not so—and among the best of these studies is one by current Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Frederic Mishkin (1982). Despite this, the “natural state” theory has been widely adopted by Federal Reserve policy makers, with enormous consequences for the framing and conduct of policy and for the way that the economy is understood and discussed more broadly. Constructing a New Macroeconomic Policy RegimeMonetary policyFull employment is key to restoring the link between wages and productivity growth. That means that change in Federal Reserve thinking and in monetary policy is at the fulcrum of an agenda for shared prosperity. Full employment interest rate policyThe first and most critical change the Fed must undertake concerns its construction of interest rate policy. Currently, the Fed hawkishly watches inflation and devotes much less attention to employment. This stance implicitly rests on economic understanding rooted in the theory of the natural rate of unemployment. Restoring proper policy weight to full employment therefore requires taking the theory of the natural rate of unemployment off the table and out of policy discourse. In its place must be put a new discourse that emphasizes full employment and rejects the notion that the Fed has no permanent impact on employment outcomes and wages. Full-employment monetary policy begs the question of what is full employment. Lord Beveridge, the originator of the Beveridge curve, defined it as a situation in which vacancies equaled unemployment so that there is a job available for everyone wishing to work. The Humphrey-Hawkins Act (1978) defined full employment as an unemployment rate of 4%. However, an unemployment metric is subject to some serious criticisms because the official unemployment rate (the Bureau of Labor Statistics U-3 measure) does not include workers who are “discouraged” or “marginally attached” to the labor force. These are workers not actively looking for work because they think they cannot find appropriate jobs. Additionally, the official rate does not include workers who want full-time work but are only able to find part-time work. An alternative employment-focused measure of full employment is the employment to working-age population ratio, which captures the extent to which the working-age population is employed. This ratio peaked at 67.1% in 2000, and that peak can serve as an indicator of full employment for the current economy. Pornography is difficult to define, which prompted U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart to famously observe “I know it when I see it.” The same holds for full employment, which is also hard to define, but we know it when we see it. Simply put, full employment constitutes a condition in which jobs are easy to find. That implies a relatively high vacancy-to-unemployment ratio, a low official unemployment rate, low numbers of discouraged workers, little involuntary part-time work, and a high employment-to-population ratio. Under those conditions, the duration of spells of unemployment will also be short since jobs are plentiful. With full employment, wage growth will also track productivity growth as firms compete for scarce workers. Currently, the Fed defines full employment as a situation of rising inflation. A better definition would be one of wages systematically rising with productivity. According to that measure, the United States has operated below full employment for most of the last 30 years. The exceptions have been the late 1970s, the late 1980s, and the late 1990s, when wages started rising with productivity at the tail end of booms. The dangers of inflation targetingNot only has Federal Reserve interest rate policy privileged concerns with inflation over full employment, there are now indications that it is moving to adopt an explicit inflation-targeting policy regime. This would entail monetary policy being guided by the goal of hitting an explicit numerical inflation target. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has written extensively in favor of inflation targets (Bernanke et al. 1997 and 1999). Moreover, a co-author of his book on inflation targeting, Frederic Mishkin, has recently been appointed vice-chairman of the Fed. Additionally, there is much support for inflation targeting within the economics profession, again showing the importance of ideas in shaping policy. Considerable damage has already been done through persistent talk about the existence of an informal 2% inflation target. This talk has coordinated the bond market and given it a focal point against which to bind the Fed. Formally institutionalizing inflation targeting would compound this damage and further entrench natural-rate-based interest rate policy. The intellectual justification for inflation targeting comes out of the Fed’s natural rate framework. This framework claims that the Fed cannot do anything about unemployment and inflation is always bad. Given that, it therefore makes sense to aim for low and stable inflation subject to retaining a margin of space to lower nominal interest rates in recessions. However, the natural rate model is flawed. The reality is that the Fed manages macroeconomic activity, and in doing so it implicitly influences inflation, the unemployment rate, and the real wage.6 It is easy to see how an inflation target policy will bias all macroeconomic policy decisions toward low inflation. If policy is framed exclusively in terms of inflation, a 2% target will trump a 3% target even if that means higher unemployment. Conversely, if policy is framed exclusively in terms of unemployment, a 4% target will trump a 5% target even if it means higher inflation. How policies are framed matters to the outcomes because it affects perceptions and politics. The reality is that Federal Reserve policy influences inflation, unemployment, and wages, not just one of those areas, and needs to create policies accordingly. Modernizing financial regulationA key feature of the new business cycle is its reliance on credit expansion and asset price inflation as sources of demand. The increased presence of credit and asset prices is the result of both financial innovation and deregulation, and with it has come several problems. First, the economy is increasingly exposed to debt-driven asset price inflation. This process is potentially unstable, and the bursting of bubbles can generate serious economic harm. Yet, because of the reliance on asset price inflation and borrowing for demand growth, the Fed is reluctant to intervene in this process. Instead, it has an incentive to put a floor under asset prices. Second, individuals are not necessarily made better off by this process. Increased house prices go hand-in-hand with increased debt, meaning individuals carry more balance sheet and bankruptcy risk. Increased house prices also mean greater interest payments on the increased debt. Additionally, increased house prices strain the economic prospects of younger workers. With regard to stock markets, over-paying for stocks can have significant consequences for retirement income. For the Fed, the problem is that it has relinquished all of its tools except interest rates. That means it must now manage activity in both the real economy and the financial sector with just one instrument—the short-term interest rate. If it uses interest rates to manage asset prices, then it risks damaging manufacturing and the broader economy, which can be termed the “blunderbuss effect.” Conversely, if it ignores asset prices and uses interest rates to manage the real economy, it risks an unstable asset price bubble and debt build-up. to continue reading article Top of page |